Thus the primary emphasis in 'iai' is on the psychological state of being present (居).

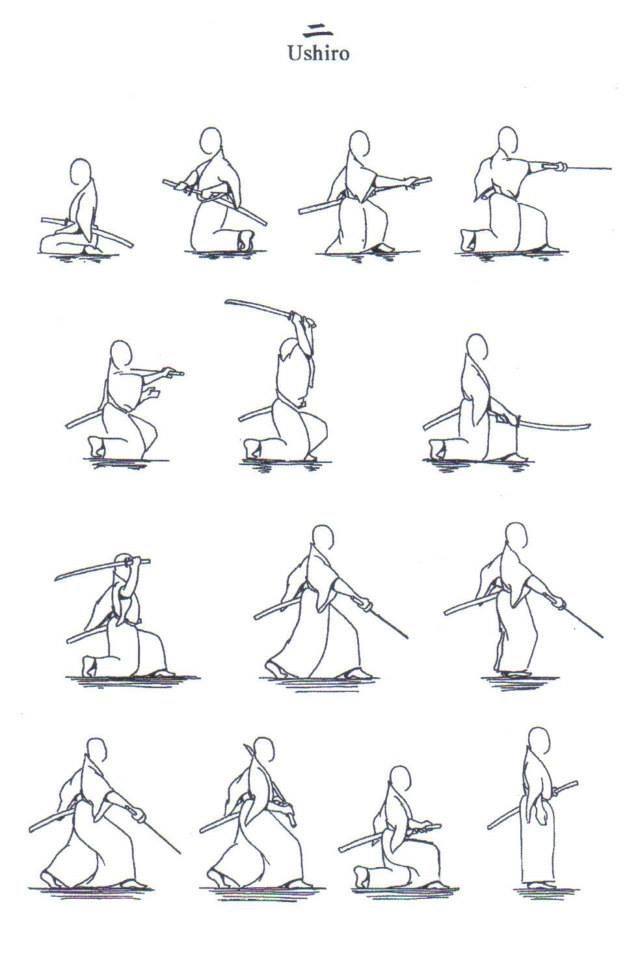

The origin of the first two characters, iai ( 居合), is believed to come from saying Tsune ni ite, kyū ni awasu ( 常に居て、急に合わす), that can be roughly translated as "being constantly (prepared), match/meet (the opposition) immediately". The term "iaido" appears in 1932 and consists of the kanji characters 居 (i), 合 (ai), and 道 (dō). If the sword is straight and true, the heart is straight and true.Haruna Matsuo sensei (1925–2002) demonstrating Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu kata Ukenagashi This is expressed in holding and manipulating the blade correctly. They are both needed and exhibit a dichotic nature when expressed in balance. In regards to the use of the sword, the right hand is the jitsu, (the real), the left hand is kyo, ( the emptiness). With each cut we aim to cut away more of our inner weaknesses and leave behind our true self. Thus, each cut should embody some realness, displayed in our careful attention to hasuji, or we are merely swing the sword, and ignoring the Bu aspect of our chosen way. Iaido is a modern budo with the goal of character improvement, but we still use a sword, and instrument solely designed to cut. We see this in the angle at which the sword is drawn, the angle of nukitsuke, of kiriorishi, and the numerous cuts in various katas. Placing an emphasis on the details is at the core of iaido practice and none more that the angle at which the blade moves. When using an iaito or shinken that has a bo-hi (a groove), the sword will not make a sound if the angle is changed while perfuming a cut. In iaido, it is paramount to focus on this to ensure that one cuts with the blade and not with the shinogi/side.

Ha-suji tadashiku is defined simply as the correct angle of the cut, particularly as it enters and exits the opponents.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)